Years ago, I tried to read a book on telecommunications protocols. I didn’t get very far before learning that there were such things as ‘protocol layers’ that made the subject a lot more complex than simply translating voltages (or light flashes) into bits. I stopped reading because in the back of my mind, I couldn’t believe that the subject was really that complicated.

Well, now I’m learning that even my simple screen-to-photoresistor GRIS communications may require more than one layer of protocol too.

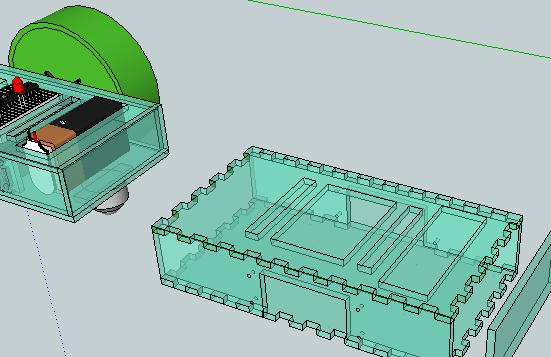

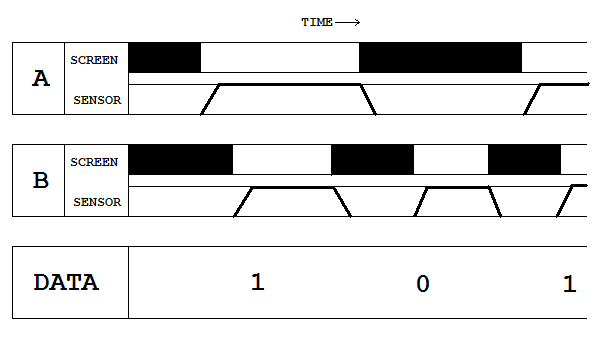

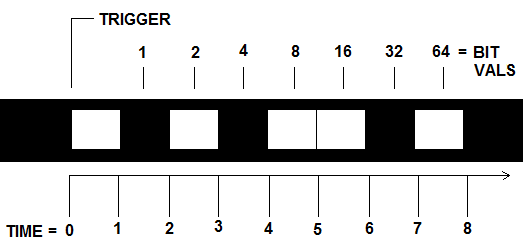

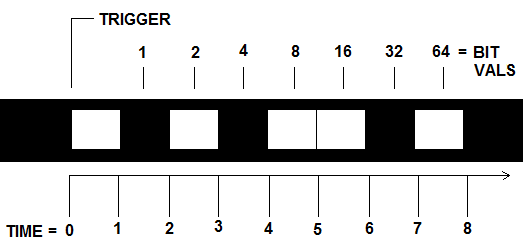

Originally, I had a single layer which assumed that screen flashes were sharp and synchronized, like so:

But then I encountered a major problem. For while the Processing computer language has a command to set the maximum frame rate, there’s no control over the minimum frame rate. This lack of timing precision is okay so long as the visual display is for human eyeballs, but wreaks havoc with a communications protocol based on time-interval synchronization. And it turns out that anything that consumes computing resources (such as merely running a browser in the background) will slow down the frame rate.

So I had to come up with a communications protocol that would allow for asynchronous communications. Since the microcontroller reads the photoresistor with a precision of better than one percent, why not use a tri-tone system to distinguish data transitions?

But then, since photoresistors are notoriously slow, what would keep a transition from high to zero being interpreted as a low value?

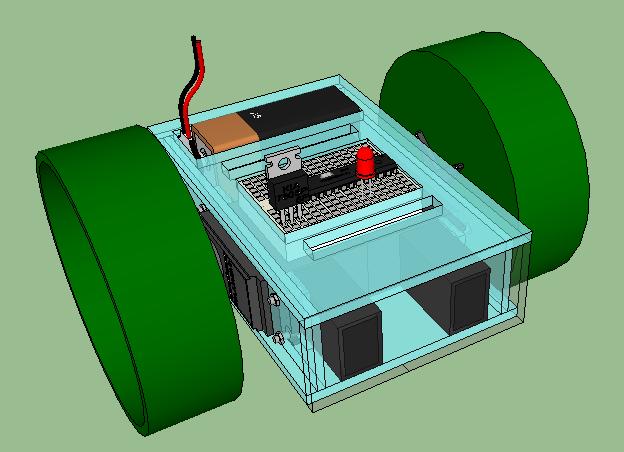

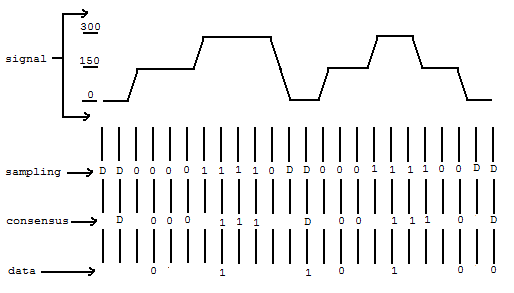

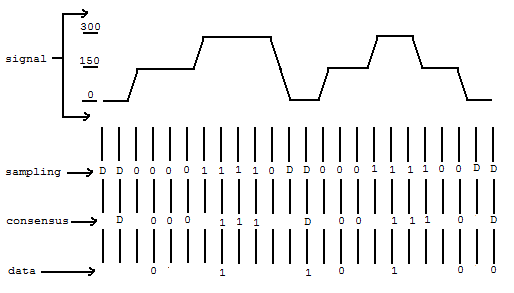

I realize I’m not explaining this well verbally, so here’s a diagram of an example signal with the three (so far) communications protocols applied (NOTE: time is the horizontal axis):

The top layer shows the signal as read by the microcontroller. The analog input is capable of reading from 0 to 1023, but I’m limiting the reading to gray tones between 0 and 300 because a full illumination transition for the photoresistor (aka Cadmium Sulfide Light Dependent Resistor) is undesirably slower.

The microcontroller sampling rate is set so that it is much faster than the screen frame rate but slower than the photoresistor transition rate. When switching from a high to zero reading or from zero to high, the sampling layer contains transient readings that must be filtered out or else they will be interpreted as low readings.

Hence the consensus layer, which requires a sampling reading to be repeated before it is recorded.

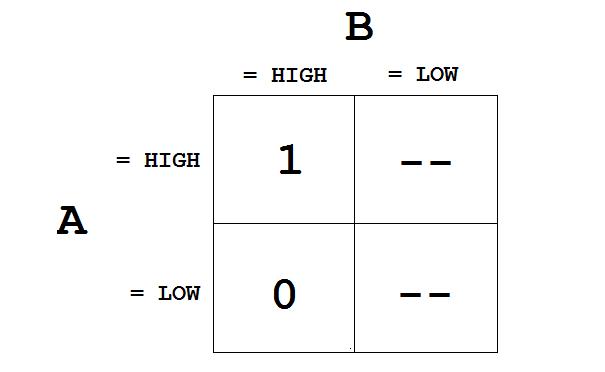

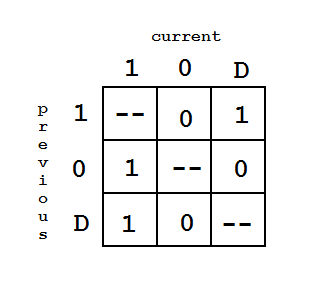

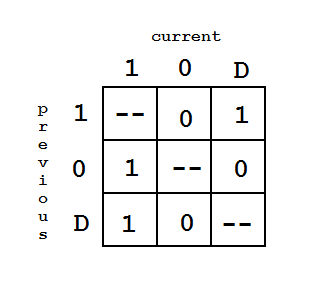

Now, the data layer is a bit tricky. I have three values — 1, 0, and D for ‘ditto.’ Because communications are asynchronous, repeated readings in the consensus layer have to be ignored. So how do you represent a 11 or 00? Well, that’s where D for Ditto comes in. If a D is encountered in the consensus layer, it is assumed to repeat the previous 1 or 0.

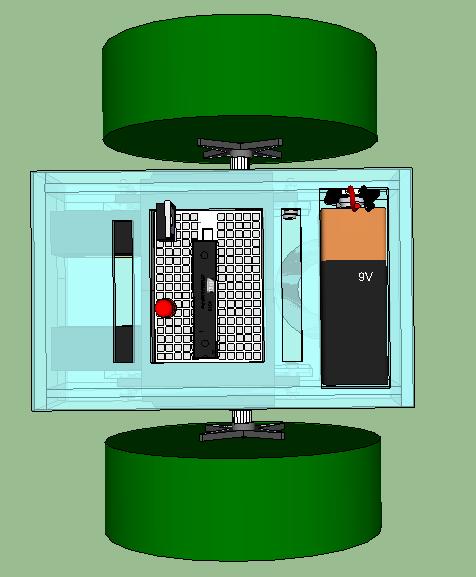

Here’s a little conversion chart which explains how the microcontroller interprets the consensus layer to create the data layer:

Have I managed to explain it? Probably not. Probably I’m not even applying the communications protocol terminology correctly. My blog is basically me talking to myself and attempting to thrash out ideas and should be read for entertainment purposes only.

Anyhow, what this system means in practice is that so long as the frame rate is slower than the sampling rate and the photoresistor switching speed is faster than the sampling rate, I should be able to accurately transmit data.

Now I just need to figure out how to write the computer and microcontroller programs for this. And uh, see if it works.