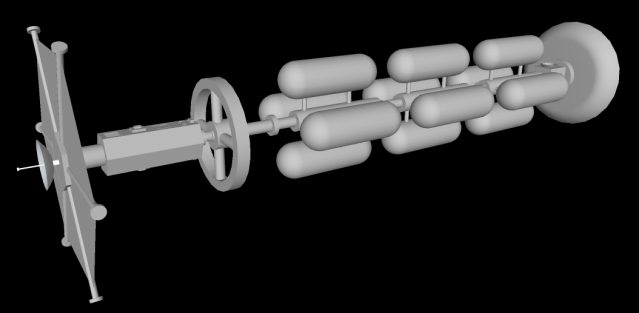

Starship Orinoco is a generation-type starship. It is fusion powered and has a cruise velocity of five to ten percent the speed of light. Hence it takes decades to travel to Alpha Centauri, the nearest star to our sun. The ship is two kilometers in length.

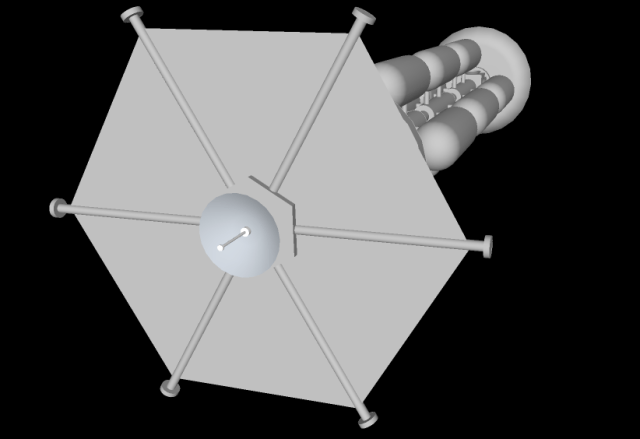

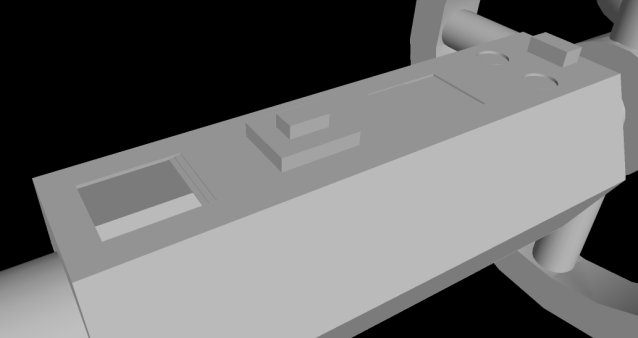

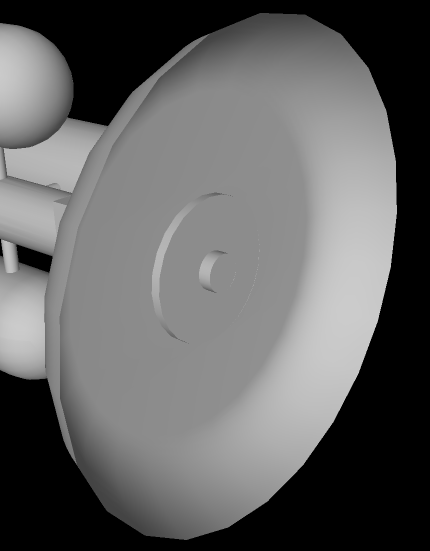

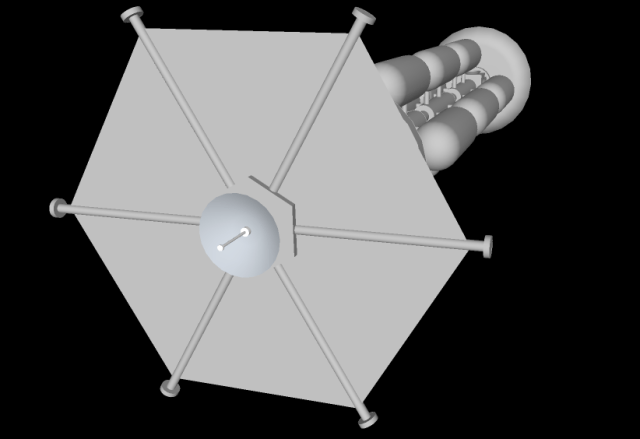

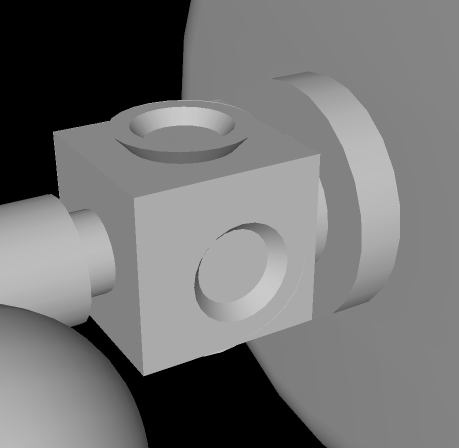

At the front of the ship is a radar to detect obstacles in the path of the ship so that they can be avoided. The hexagonal screen is charged to generate a powerful electromagnetic field around the ship to deflect the impact of micrometeorites. Side and rear radar are located at the tips of the projecting struts.

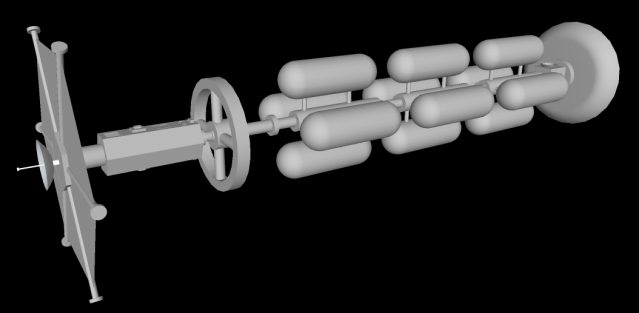

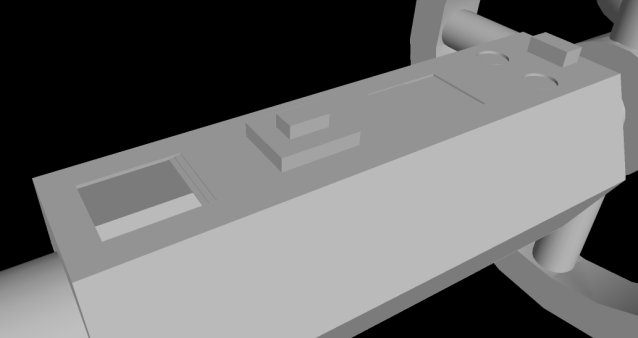

The service module contains hangers for shuttle craft used for travel between the starship when it is in orbit around the destination planet and the surface of the planet. There are also pod bays for probes, tugs, and various types of robots. Most of the module contains cargo and supplies for the colonists when they reach the destination planet.

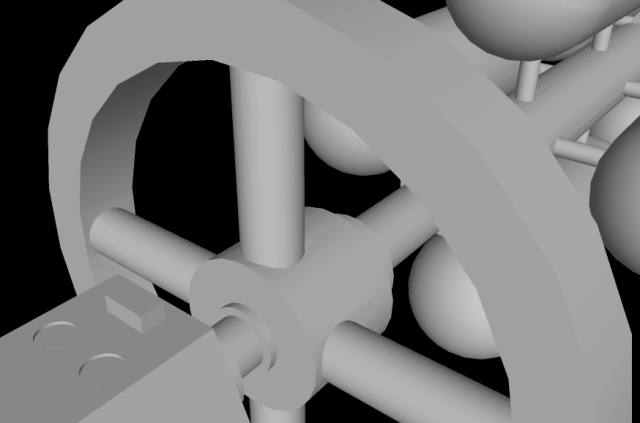

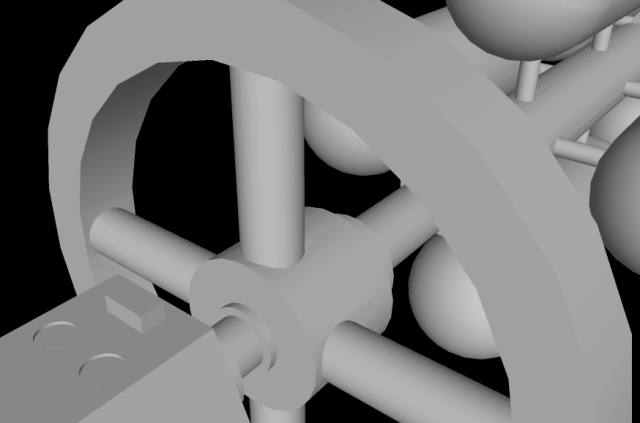

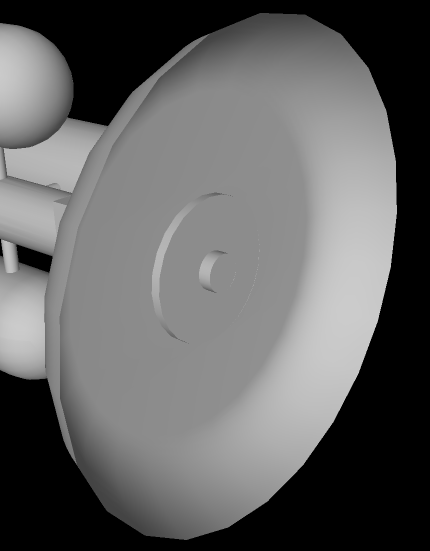

The habitat wheel is where the passengers will while away the decades in transit between star systems. It rotates to provide one-third earth gravity and is three hundred meters in radius. With multiple levels, it provides over a million square meters living space for a thousand passengers.

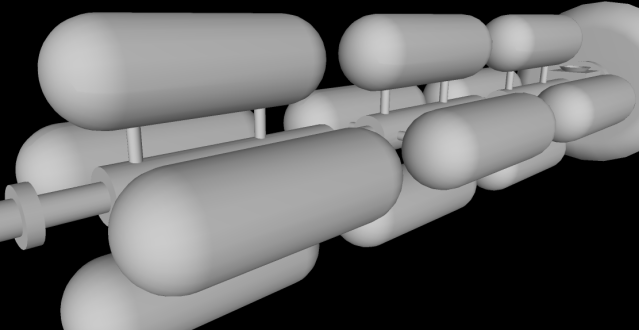

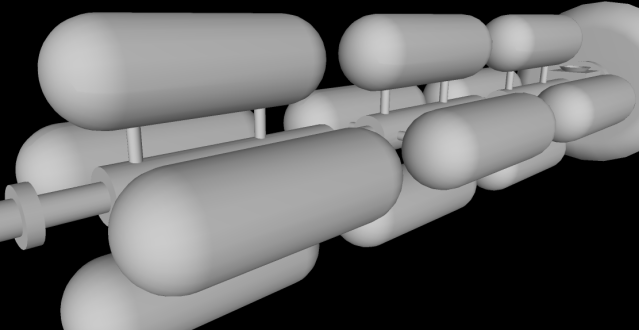

Modular fuel tanks are filled with deuterium for the fusion reaction. The long boom between the passenger wheel and the engine is reminiscent of the spaceship Discovery in the movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Four thrusters enable the starship to maneuver pitch and yaw for navigation purposes. The ship adjusts roll with an internal flywheel.

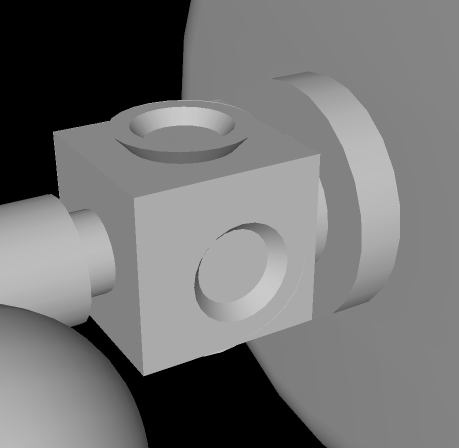

The engine has a ‘pusher-plate’ design reminiscent of Project Orion, in which deuterium pellets are launched behind the ship and fusion ignition is achieved with lasers and magnetic fields. Maximum acceleration is .01 g and it takes years to build up to cruise velocity.

Orinoco is pictured here traveling alone across the interstellar void but is likely to be part of a fleet of two or three other similar ships. It also has fleets of probes to venture millions of kilometers ahead of the ship’s path in order to detect and avoid obstacles such as asteroids and meteoroids.

Probably, such ships are the stuff of the twenty-second century, or beyond, but it’s fun to dream. And who knows, if medical science continues to extend human lifespan, people who are alive today might someday venture to the stars.

Interstellar Travel at Amazon